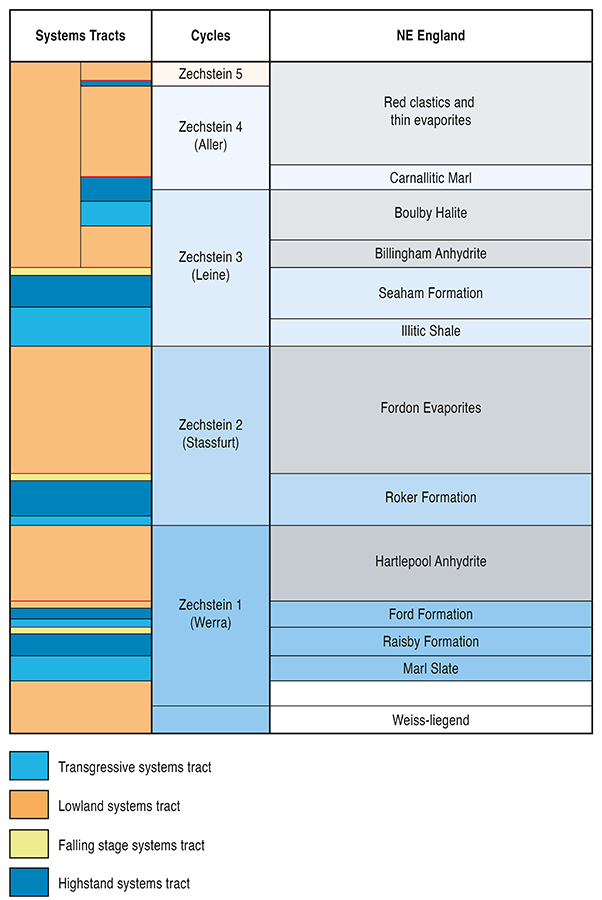

As we approach the Gin Cave at Blackhall, we’ll explore the different features of the Permian limestone formations: Ford, Roker, and Seaham. All of these formations are composed of limestone, making it challenging to distinguish them along the cliff.

One factor complicating the stratigraphy at Blackhall is faulting, which has disrupted the vertical arrangement of some formations. For instance, the Seaham Formation, which should be at the top, is found lower in the cliffs near the Gin Cave. Thus, the order of the Ford, Roker, and Seaham formations might not be as expected. Nonetheless, we’ll try to identify the unique characteristics of each formation during our walk. These formations were deposited through various processes, with some in deeper water, others along the reef rampart, and some in the intertidal lagoon behind the reef. Each process has contributed to the formation of distinct features visible in the cliffs. On the south side of the Gin Cave, we see the Ford Formation (the boulder conglomerate). Just above lies the Roker Formation, recognized for its crinkly beds and stromatolites.

Dolomites: Historically, the Upper Permian rocks in County Durham have been referred to as the Magnesian Limestone, that is magnesium-rich calcite. However, these days we would call these rocks dolomites, since they are composed of that mineral rather than calcite. The sediments would originally have been precipitated as CaCO3 but they were dolomitised by refluxing seawater and hypersaline water soon after deposition. Original limestone is only present in the lower parts of the Raisby and Ford Formations, and locally in the slope sediments of the Roker Formation. In some places, the dolomites have been altered back to limestone, a process called dedolomitisation. This occurs in some parts of the Roker Formation in particular, well seen in the area of Marsden.

360 Degree Interactive Panorama